Maine entered the United States as a result of the Missouri Compromise. This was the first national-level agreement to keep the United States from breaking apart under the weight of slavery. The U. S. Congress admitted Maine and Missouri together to maintain an equal number of slave and free states: Maine would enter as a free state, not allowing slavery, while Missouri would enter the Union simultaneously as a slave state, allowing slavery. Neither side wanted to let the other gain a political advantage. Many Northerners also objected to the expansion of slavery on moral grounds.

The resulting political turmoil almost disqualified Maine’s bid for statehood. After decades of fighting for independence, it now seemed the crisis over slavery would force Maine to remain a district of Massachusetts even longer. The Massachusetts legislature had set a tight deadline for Maine to enter the Union or else revert to district status.

A vote for the Missouri Compromise was a vote for the expansion of slavery. A vote against it was a vote against Maine’s statehood. Five of the seven Massachusetts Representatives for the District of Maine voted against the Missouri Compromise in an effort to limit slavery. Nevertheless, it narrowly passed in the House of Representatives, and Maine became a state.

Regardless of how one felt about slavery, much of the nation’s economy relied on slave-raised products such as cotton, sugar, and molasses.

Slavery was legal in every American colony, including Massachusetts’s District of Maine. In 1783, Massachusetts was the first state to outlaw slavery, but the regional economy still depended on shipping, which involved slaves and slave products.

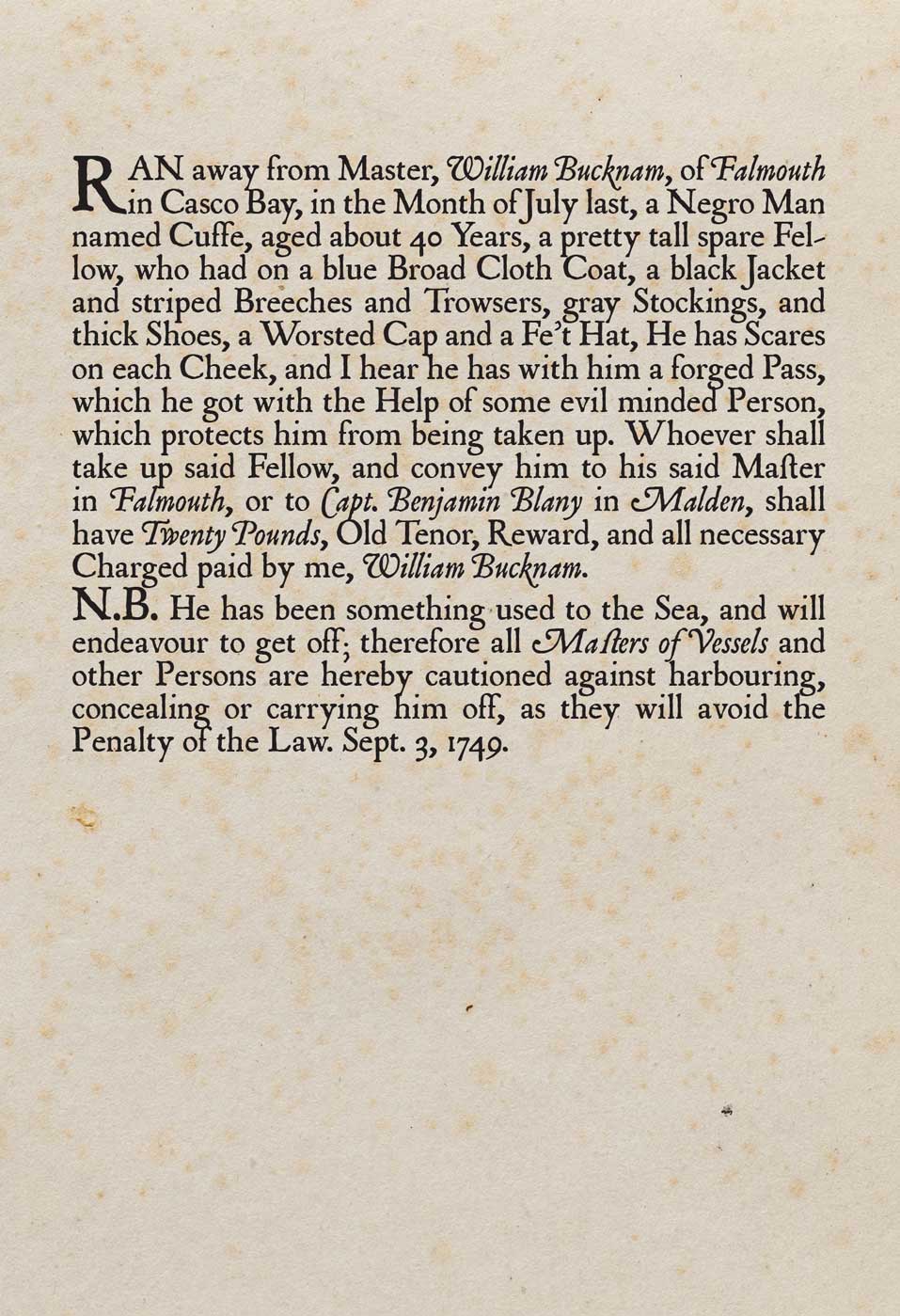

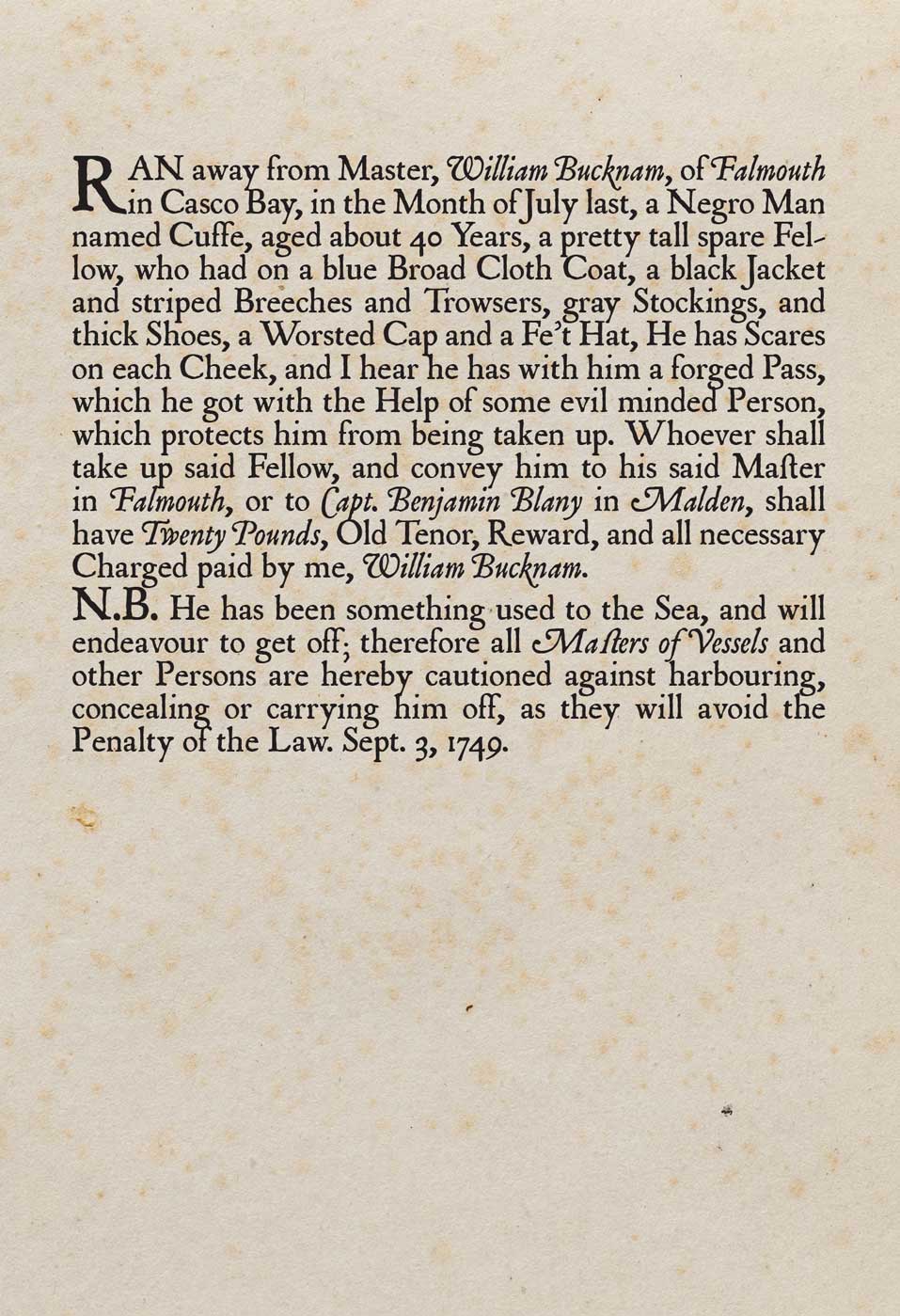

Boston Evening Post Fugitive Slave Advertisement (reproduction), By William Bucknam (1709-1776) of Falmouth (Portland), Boston, Massachusetts, September 18, 1749

Wearing silk, like owning slaves, was a sign of prestige.

John Bucknam was raised in a slave-owning household in Falmouth (Portland). When he was three years old, his father William’s slave, Cuffe, ran away. William advertised in three Boston newspapers to offer a cash prize for anyone who caught and returned his property. Cuffe may have successfully escaped because the first runaway notice appeared in 1749 and the last in 1755.

John Bucknam wore this silk waistcoat (vest) in 1773 when he married Mary Wilson in Columbia Falls, Maine. He and Mary had nine children and owned two or three enslaved people. The Bucknams were forced to free their slaves when Massachusetts outlawed slavery in 1783.

Wedding Waistcoat (Vest), worn by John Bucknam (1746-1792), Columbia Falls, Maine, 1773, Maine State Museum, Gift of John Bucknam Drisko, 79.95.1

John Bucknam wore this silk waistcoat (vest) in 1773 when he married Mary Wilson in Columbia Falls, Maine. He and Mary had nine children and owned two or three enslaved people. The Bucknams were forced to free their slaves when Massachusetts outlawed slavery in 1783.

Slave labor fueled the national economy. Every American consumed slave-raised products such as cotton, sugar, and molasses. The people of Maine were no exception. In fact, Maine led the northern states in the production of cotton fabric in 1810. Cotton was the primary slave-grown crop cultivated in expanding plantations throughout the south. Maine traders purchased cotton to be processed into fabric by home weavers throughout Maine and resold elsewhere.

Sugar Bowl, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1820, Maine State Museum, Gift of James H. Phelan, 70.18.9

Sugar Tongs, made by Enoch Moulton, Portland, Maine, 1805-1820, Maine State Museum, Gift of Charles Burden, 80.111.65

Sugar exploded in popularity as slave labor made it an inexpensive commodity in the early 1700s. By 1800, sugar growth and production in the West Indies accounted for more than 80% of the slave trade and nearly half of all seagoing shipping. The West Indies relied entirely on the American colonies and Europe for fuel and other supplies.

Enslaved workers grew and cut sugar cane under brutal conditions. Each plantation had a sugar mill. Slaves worked the mills that crushed the sugar cane and boiled the cane to extract the sugar, leaving molasses as a by-product. Maine timber fueled the fires that boiled the sugar.

Nearly all Atlantic commerce played a role in the slave trade. Maine shipbuilders and shipmasters contributed to the “triangle trade” that carried products and enslaved people between the Americas, along with the West Indies (Caribbean Islands, including individual islands such as Cuba, Jamaica, and Haiti), Europe, and Africa. Exporters in America shipped raw materials to Europe where they picked up trade goods. These trade goods were taken to Africa and sold in exchange for slaves to be brought back to the Americas.

West Indies plantation owners purchased great quantities of Maine trees, felled by axes similar to this example, to fuel the boilers that distilled sugar cane into refined sugar and molasses. Enslaved people worked around the clock in hot and dangerous conditions to keep the fires burning. By 1700, most trees in the West Indies had been cleared to make way for sugar fields.

Felling Axe, 1700-1800, Maine State Museum, 00.74.1

In 1808, Congress outlawed the international importation of slaves. Although American ships could no longer legally carry enslaved people, Maine ship owners grew wealthy as they continued to provide ships and sell firewood to the West Indies.

Maine products supplied plantations and linked Maine to the triangle trade. Maine seaports prospered as ships laden with timber and salted fish departed to supply West Indies sugar plantations, linking Maine to the triangle trade. Ships sailing from the islands brought sugar and molasses back to New England, and cotton from the American south. Molasses was used to make rum, some of which was traded in Africa for slaves.

John Rice Robinson Tavern Sign, Mount Vernon, Maine, 1804, Maine State Museum, Gift of Margaret R. Webber and Lois Webber Williams, 69.91.1

Taverns throughout New England sold rum. John Rice Robinson would have acquired rum for his tavern from the seafaring ships docked in Hallowell, Maine on the Kennebec River. Rural merchants and innkeepers lined up their wagons at the wharves ready to load rum and other products imported from the West Indies to be sold in inland towns.

When the choice came between statehood and accepting slavery, many Mainers preferred to limit slavery. Although Maine’s economy was deeply connected to the international trade that fueled the expansion of slavery, many people had a deep distaste for slavery and opposed its existence, let alone its expansion. Delegates to Maine’s state constitutional convention agreed that free men of African descent could vote in the new state, even though this was a time when many other states were revising their constitutions to ban black voters. When Maine’s statehood became tied to slavery’s expansion, it posed a grave dilemma for the seven U. S. Representatives from the District of Maine. In the end, only two of the seven voted in favor of Maine’s statehood. The other five could not bear to vote in favor of expanding slavery in America, even if it meant losing the opportunity to become an independent state.